11 May 2021

Published in Amsterdam Alternative Issue #030 : May - June 2020

Special Thanks to Amsterdam Alternative, Nicole Go, Stijn Verhoeff, Thijs Witty

Read here : https://amsterdamalternative.nl/articles/9440

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE MARKS OF ERASURE ON A SOCIETY IN CRISIS? A REFLECTION ON THE 2019 HONG KONG UPRISE

The Corona crisis is turning life upside down, or inside out, and will change the world as we know it. Still, I never want to forget what happened in 2019 in my hometown Hong Kong. Mid December, while in Wuhan, China, the first people started to die from their long infections, I returned to Hong Kong amidst the aftermath of mass marches on the central business district.

The events, beginning with the anti-extradition bill protest, marked six months of turmoil that fractured the city. As is usual during marches, protestors left hundreds of thousands of instances of anti-government graffiti across the roads, walls, street signs and bus stops. Once impassive, the pair of bronze lions guarding the HSBC headquarters now bears the messages of the people’s steadfast heart.

The months of the pro-democracy movement in June 2019 have resulted in an avalanche of online photographs and videos: images of violence and of propaganda bearing witness to the shocks to the cityscape. When walking around town, one can find themself surrounded by what French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s described as the state of being “under erasure” (sous rapture). This concept is related to writing, and means “to write a word, cross it out, and then print both word and deletion.”1 Smudged or semi-erased protest graffiti is the mark of the presence of what the government usually makes sure is absent from public life. This graffiti is an announcement that the opposition, that Hong Kong democrats, exist is a state of sous rapture.

As Derrida writes: “The trace is not a presence but is rather the simulacrum of a presence that dislocates, displaces, and refers beyond itself. The trace has, properly speaking, no place, for effacement belongs to the very structure of the trace […] In this way the metaphysical text is understood; it is still readable, and remains read.”2 Although this enigmatic description of the trace is imbued with significance for his philosophical argument, the passage also works in a more literal sense when applied to Hong Kong.

The traces that remain after a supposed erasure - Hong Kong residents “return” to an altered cityscape only after suffering political violence - fascinate me. Erasure is never an act of making things disappear completely, for it leaves remnants in its aftermath. There are reminders of the violence involved in altering a city and its people. I wonder how these traces manifest themselves and contribute to the possible future of the society.

The doing and undoing of protest graffiti

During the week following my own return to HK, in pursuit of signs of ‘erasure’ I visited the areas where the most prominent protests had happened.

The various ways in which protesters have altered existing urban spaces for their cause, in defiance of norms and regulations, runs parallel to their pro-democracy demands. Graffiti of both Chinese and English slogans can be found on almost every sidewalk, crossroad, footbridge, building exterior and subway station. The most common graffiti is “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times,” sprayed in traditional Chinese, which is the official written language in Hong Kong. Other messages include the popular chant “Five Demands, Not One Less,”3 expressing the calls for democracy, and a trending hashtag “CHINAZI,” a portmanteau of China and Nazi.

Graffiti, especially anti-government messages, is typically frowned upon in a cosmopolitan financial centre like Hong Kong. The island’s government champions stability, as this is intimately tied to efficiency. After every mass march, street cleaners work around the clock to erase the protestors’ graffiti by the order of the bureaucracy, which sees these messages as both remnants of conflict and a provocation to confrontation. To erase them is, as government propaganda says, to restore the city’s normality.

While most young demonstrators are only novices when it comes to the art of protest graffiti, so are the street cleaners. The cleaners, many of whom are middle-aged or elderly, work for the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department or one of its five, outsourced service contractors. The cleaners’ standard duty is to sweep the streets, collect waste, wash public toilets and keep the city clean in general. The strategy that they employ is pretty elementary: hastily removing graffiti by painting over it with bleach, washing it off with a high-pressure water gun, or, failing that, taping over the graffiti with sheets of black or white plastic.

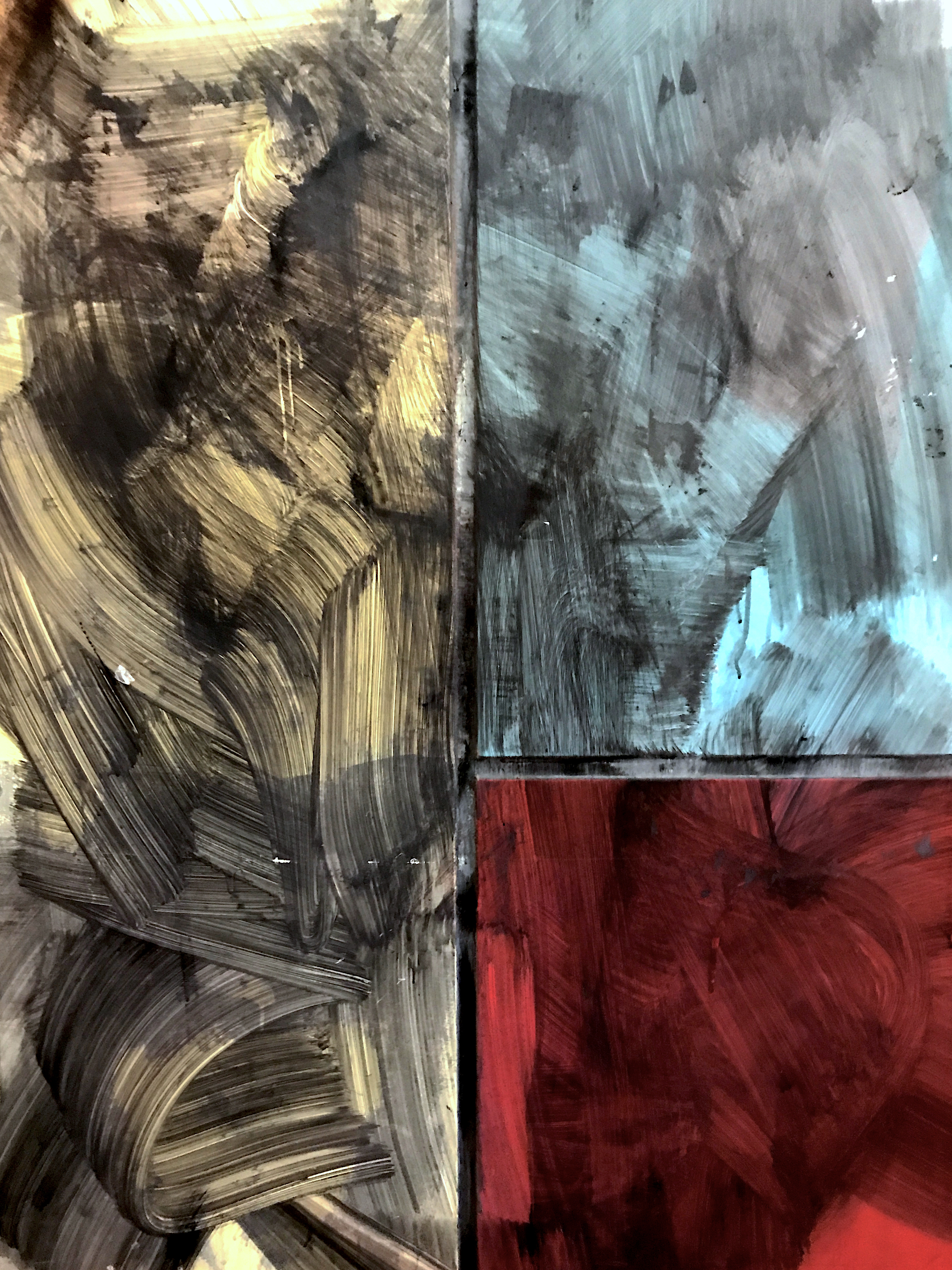

Walking along Queen’s Road Central, one can see protest messages on building facades and billboards. They are legible, despite the fact that they have been painted over, covered up, or smeared. The clean-ups have left obscure traces of prominent phrases.

The act of erasure has left the messages barely visible, but not completely washed away. Almost all of the original messages have been lost, but looking at them from across the roads, they are reminiscent of classical Chinese ink-wash brushstrokes, or expressionist paintings, both of which seek to capture the essence of life rather than a visual reproduction of the reality. With this I can associate the cleaner’s swipes with the essence of oriental martial arts.

Protestors wrote over these smeared slogans. The different coloured inks of the messages are superimposed, creating striking ‘paintings’ in the process. These ‘paintings’ require two ‘artists’ who represent the two poles of the political situation: the protestors and the cleaners.

Not far from the tram stops around Wan Chai MTR station, protest graffiti is barely veiled by white plastic sheets, whose surfaces are also painted upon; soon this too is erased with a patchwork of tape. This is a perpetual process of scribbling and scrubbing, doing and undoing.

That the act of erasing these emotionally-charged protest messages results in something so evocative is impressive. These expressive paint marks condense the essence and energy of the situation in town onto the city as canvas, signifying the various terms running through this period: upheaval, collision, rage, and resistance, collective desire.

Restoration to normality or revelation of cruelty?

As months go by, protesters are turning to more aggressive tactics to defend themselves against the escalating violence and brutality exerted by the authorities. These new tactics include vandalism of metro stations, storefronts and restaurants with close ties to China, and the un-fencing of swathes of pedestrian paths. Public spaces, whose function we take for granted, have all of a sudden become sites of protest. The city’s iconic reddish brown bricks, dug up from pathways, are among the most popular materials that have been fashioned into makeshift barricades throughout the protests.

In response to these urban-scape changes, or, as the authorities say, “unacceptable destructions,” defensive measures have sprung up in the city, which again create only more peculiar ‘traces of erasure’. Many subway station entrances that used to feature glossy, transparent glass facades are now clad in opaque steel fortifications, resulting in a futuristic outer space aesthetic. Other stations, banks and shops are encased in dark iron boards – protesters also coat these new canvases with vivid graffiti and posters.

One afternoon, I found fresh cement poured into dozens of holes on the ground on a sidewalk in the city’s busiest business and tourist shopping area Tsim Sha Tsui. This is where protesters had dug up bricks. Someone had scribbled “Free HK” before the concrete hardened, perfectly immortalising an act of resistance, that type of act the government is trying to cover up.

Marks of erasure as a testimony?

As the protests rage on along with violence and more collisions, I wonder how many of these traces will make it to the end, how many of these marks will bear witness to the writing – and un-writing – of the city’s memoir. There are sites of key moments in the protests that are now remembered as city landmarks. “This is where the 17-year old teenager was shot; this is where the man in a yellow raincoat once stood, before falling to his death as a final act of defiance and leaving behind his iconic banner; this is where a teargas canister dangerously landed right in the centre of the crowd.”

The markings throughout the city inevitably tell an important story, even if they may be eyesores to some. Should we obliterate all these scars, restore this physical damage or, as some may suggest, preserve them as a part of the city’s history, an important heritage? But what can we do with these traces? And how do we handle their precariousness? Vandalism, despite its destructive agenda, can also be understood as a phenomenon that is worth examining in relation to the city’s landscape and history. When certain kinds of damage emerge in the city, both the government and residents should examine why people felt the need to do what they did. What can we do to salvage or preserve these marks, or even give them a potency beyond the event of their emergence? How do we memorise resistance?

As a witness to these traces of erasure around the city, from scrubbed-off graffiti to repaved sidewalks, I begin to understand these marks as a subtle testimony of what happened. These traces are cultural expressions that serve as a response to crisis, a way to look trauma in the eye without having to represent violence in atrocious images. When violence as a problem is made visible through a paranoid exposure - stressing on a pre-emptive knowledge of a possible violence, believing on the idea that when a piece of information or idea becomes more and more transparent, then and only then will there be any significant effects - that exposure may changes it and expands it, very often also problematises it. Susan Sontag wrote that: “For a long time, some people believed that if the horror could be made vivid enough, most people would finally take in the outrageousness, the insanity of war.”4 There is sometimes this paranoid assumption that people have to see the painful effects of their oppression, poverty, or deludedness sufficiently aggravated as the only way to “validate” and “awaken” the consciousness of the pain, so as to emphasise on the intolerable situations as if the more intolerable it is, the more efficient to generate “solutions”. However, when we try to discuss the topic in which violence and the brokenness of subjects are abundant and spectacular, do we always focus only on the relationship between visibility and recognition? Blatantness doesn’t necessarily lead to recognition, not to mention reconciliation. To me these subtle testimonies might function as an alternative approach, one that approaches reconciliation outside a juridical economy of truth.

Along the way, traces of erasure also agitate history that has been written and communicated, its dominant narratives and prevailing discourses. When traditional history is often written in a reductive manner to what is selected, manipulated and approved by the authorities, especially in a totalitarian regime – which in many cases are a chronology of glorification as well as victimisation - these trivial traces help one to remember and explore the uncharted territories of history. They are an art form against obliteration in a multi-faceted society, whose collective memory is constantly hijacked and breached. They are a genuine attempt to preserve important parts of our truths.

As Thomas De Quincey says in Confessions of an English Opium Eater, “There is no such thing as forgetting possible to the mind.” The submersion of experience in memory is a text erased or overwritten. In the context of Hong Kong, intense demonstrations of the past year have already dotted permanent marks on the city’s landscape despite their retreat. The pro-democracy movement will change the entire narrative of the city. These traces of erasure function as emblems of fact or scraps of evidence to support the assertions of history. They serve as structural links between historical events, memory and aspirations, between what is made to be educated as facts and what is needed to be remembered. The surface of erasure always conjures a reminder of some primal violence; the eliminated facts will always be evidence of a repression of some kind, be it physical or political.

Epilogue

As Hong Kong ushered in a new year a new strain of life-threatening disease has swept the globe. The dreaded pandemic and the accompanying social distancing and lockdown have put a stop on street demonstrations in Hong Kong, but it is too early to assume the protest movement has gone away.

It wasn’t until I started writing about these visible marks of erasure that I realised the question of technology is indeed essential in our contemporary experience of traces. I started to think about digital traces, the innumerable pictures and videos that were circulated on media platforms, fleeting and ephemeral, during the protests. They are in fact one of the strongest and most powerful traces that we can hold on to, in spite of them being repeatedly censored and removed from the internet.

For many activists in Hong Kong, the coronavirus-enforced hiatus has given all a chance to regroup and to prepare for future waves of demonstrations and protests which are to be expected once the pandemic is resolved. Perhaps it is because the organisation and discussion of the entire movement was started on online platforms, in a collective yet leaderless manner, that people have long adapted to thinking about movement while online. The pro-democracy movement at this stage has only been transformed, thanks to a total lack of confidence in the government’s coronavirus measures.

As I write, new traces are being created online, despite the chance of being ‘reported and deleted’ for leaving such messages online. People in Hong Kong are actively disseminating news about the virus via social media, especially information that has been “suppressed by international organisations, China and Hong Kong Governments.”

1) Gayatri Spivak, “Translator’s Preface” to Derrida’s Of Grammatology, XVII.

2) Jacques Derrida, Speech and Phenomena: and other essays on Husserl’s theory of signs, trans. David Allison (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1973), p.156

3) The five demands are: full withdrawal of the extradition bill, a commission of inquiry into alleged police brutality, retraction of the classification of protesters as ‘rioters’, amnesty for arrested protesters, and dual universal suffrage for both the Legislative Council and the Chief Executive.

4) Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003

Photo by Ng Kang-Chung on The Star Onine

Photo by Ng Kang-Chung on The Star Onine

Photo screen-shot from a circulating video documentation on Twitter (link removed)

Photo screen-shot from a circulating video documentation on Twitter (link removed)Download issue #030 as a pdf

Or check it out on Issuu

24 April 2020

The Best of All Possible Worlds, according to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

1. Best of all possible worlds, in the philosophy of the early modern philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, is the thesis that claims the existing world is the best world that God could have created. His argument for the doctrine of the best of all possible worlds is now commonly referred to as Leibnizian optimism, which was devoted to defending the justness of God in a system combining the Orthodox religion and modern logic.

2. The problem of evil is conceivably the most intractable problem when the theist is argued against his proposition, especially when we are long convinced to believe in an omnipotent and loving God. For Leibniz, the presence of evil does not equal only the absence of good. Evil to Leibniz, is a necessary state of affairs to allow for some greater good that has yet to appear. By the Law of Sufficient Reason claimed by Leibniz, nothing happens without a reason why it should be so rather than otherwise. God for the same reason wouldn’t have acted less perfectly than he could have. In this case the existence of evil is justified, but provisionally, since it is compossible with and must be accompanied by a greater good - which also includes by tolerating certain evil avoids a greater evil.

After all, why it is regarded as the “best of all possible” by the Divine may have very little to do with human beings. As one of the many living species in this world, we undoubtedly have only a limited perspective on ‘things’. What seems unnecessary to us may be necessary precisely because it is the only thing compossible with the maximal amount of goodness. The universe is created in a state of pre-established harmony. It is inconceivable and impractical for us to speculate what gauge does God use to measure ‘goodness’, Leibniz hence pointed out that within God’s comprehensive providence and within a divine standard of goodness that differs from ordinary human conceptions of that notion, God must optimise maximum perfections for the entire world.

3. Amongst all skeptics and atheists who lampooned Leibniz, Voltaire criticised clearly in Candide - ‘All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds’ was merely absurd when set in the backdrop of unrelenting series of violent injustice and massive disaster like the Lisbon earthquake happened at heir times. Candide was absolutely right, this world seems to be lousy at times, anyone could improve on it, one less crime, one less murder, one less child being abused and so on, would make it already a better world. Let me try to speculate how Leibniz might have responded : To those who think it is unlikely that our world contains the greatest possible amount of goodness, it is only because they have not, and cannot wait until all the facts are in. The world includes not only all the events that have happened and are happening now, but those that are yet to happen, including those in the afterlife perhaps. When we think of ‘this world’ as the best of all possible worlds, what we we referring to as ‘this’ time-space? This leads me to recall a metaphor that Milan Kundera once used to explain life :

“There is no means of testing which decision is better, because there is no basis for comparison. We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold. And what can life be worth if the first rehearsal for life is life itself? That is why life is always like a sketch. No, "sketch" is not quite a word, because a sketch is an outline of something, the groundwork for a picture, whereas the sketch that is our life is a sketch for nothing, an outline with no picture.”

― Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

4. It is beyond dispute that we may ever find out what criteria God used to determine ‘good’, hence according to Leibniz, how can anybody say we are not living in the best of all possible world? In this case the burden of proof is on the person that claims otherwise. For someone to challenge and refute that we’re living in the best of all possible worlds, they have to prove that that’s the case. If there’s nothing that can possibly count against a view, then on what grounds can we be sure about something, about anything? Let’s now return to the popular proverb: “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” The proverb is unsophisticated, but it somehow confounds the wisest who wouldn’t know more on these first principle matters than the most ignorant.

After all it is indeed reasonable for us to worry about, regardless that there are many things that human will not be able to fathom - so how much suffering can be absorbed by this conception that we are too limited to perceive a full picture of the world’s well-being? At what point do the appearances overwhelm or tip the balance in favour of the skeptical conclusion instead of this sort of confidence about faith - a faith that we are inadequate to comprehend the world? To a certain extent this involves an ethical issue. In many cases, we have learnt to beware of arguments that incorporate our ignorance into their defence. Politicians, salesmen, internet scams and counting, whom may be disguising or misleading us deliberately, or trying to win our trust but in fact they are constructing something deeply amiss.

5. It is not that hard for us to understand that the best isn’t necessarily equivalent to perfection - the best of all possible worlds does not guarantee a perfect world. When we said ‘I’ve tried my best’, we most of the time do not mean that we’ve performed perfectly. With typical modesty, we say so believing that there is always still room for improvement. However we do have to be sensitive and sensible enough not to be muddled up ‘the best of all possible’ as in ‘All is well’. Admitting that this may never be the ‘perfect’ world of quotidian pleasure, we should not simply settle in the contentment of living in the best of all possible worlds. Thinking in terms of politics, social orders and power struggles, what are the implications if a deviated principle of thought from The best of all possible worlds is being promoted in our culture at large? All is well - The gap between ideality and reality is ceased, our criticality and analytical judgments towards the state or the society is deprived - because we are living in the best of all possible worlds and all is for the best. The intellectual's job is thus left to make sense out of this idiosyncratic situation, or, to criticise systems and individuals that are not willing to align.

6. The best of all possible worlds is in fact a non-disconfirmable hypothesis - we cannot, in principle, prove or test it either way. There is no evidence that might ultimately reject or disprove it. To me a non-disconfirmable hypotheses are suspicious for the same reason conspiracy theories are, precisely because of this reason I would not wish to dig into its ‘truth’, but how we could possibly transform the piece of information in lieu. Whether the existing discrepancies between the theory and fact should be increased, or diminished, or what else can we do with them, will generate comparatively more constructive impacts in improving the world that we are inhabiting in.

As proposed in her introductory notes, Isabelle Stengers states that the ecology of practices is not a general metric that can be applied widely, instead it is a ‘tool for thinking’ in the middle of divergent and incommensurable worlds. Thus, to treat the ecology of practices as a tool means that it acquires its meaning in and through its use. We do not know what this tool means until it is put to work and gives the ‘situation the power to make us think’. (185)

I could totally understand her viewpoint in claiming that the ecology of practices, as she defines it, is Leibnizian. By saying so she has also transformed the notion of The best of all possible worlds into a way of thinking, which in my opinion gives an alternative yet purposeful elucidation of the idea - Indeed we cannot affirm our world is the best without becoming, without being transformed by the obligation to feel and think all that this affirmation entails. The idea has now much less to do with as a matter of faith but as a testing experience. As a tool of thinking it does not guarantee a resolution to all and every circumstances, it can be implemented whenever and wherever applicable.

7. I would love to re-think about the Best of all possible worlds in an absurdist’s manner, though slightly twisting the rational principles. Inspired by the pioneer of Absurdism Søren Kierkegaard who said, ‘As the reality of God is beyond human comprehension, it is absurd for humans to have faith in God.’ And whether we have this faith or not is a decision we make that lies outside reason, a decision we can make individually for ourselves. That ‘leap of faith’ is not primarily a function of our rational capacities but also our will and our trust. Adopting the frame of minds from the absurdists who embrace the search of answer in an answerless world, can we then apprehend the notion the Best of all possible worlds as an approach to give life a possible meaning? We on one hand can live with the knowledge that our efforts will be largely futile, this will never be a perfect world, our lives soon be forgotten, and our species will irredeemably corrupt; on the other hand we should endure and it may be worth enduring nevertheless. As in Albert Camus’ famous formulation, ‘One must imagine Sisyphus happy’. While acknowledging the absurd background of existence and attempting to triumph the constant possibility of hopelessness, maybe this idea of nothing has a true meaning can be a liberating and constructive one for us to continue our lives on a far-from-best-of-all-possible world.

By employing either a seemingly optimistic or absurdist way of thinking, we may be able to liberate ourselves from the everlasting debate and exhaustion on truth-digging, which may not take us any further at the end. Alternately as a potential, not a statement - then what if we are living in a world of the best of all possible ways to get to the best of all possible worlds? Even if you believe that this is God’s best of all possible worlds should not exonerate you from trying hard to rectify its shortcomings (injustice and suffering); not that you can turn this world into a paradise, but there is the opportunity to make this world as liveable as possible.

If we consider its potentiality and settle on the necessary precondition of the best of all possible worlds - that higher-order virtues will not be produced without allowing the lower-order virtues being permitted, we may land on a different position in looking at disasters, which can be at times a reparative approach. For instance, allowing sin permits the possibility of forgiveness and refinements. As suggested by writer Rebecca Solnit, while hurricanes, tsunamis and earthquakes are the least to be wished for, yet these disastrous events in history have many times elicited human’s best responses and provide common purposes and connection across nations. Not to mention numerous causes of earth’s disasters have roots in actions that we humans undertake on the planet to satisfy our wishes and in turn leading to mass suffering among all living beings. Solnit fully explicates the potentiality of what is concealed in the idea of The best of all possible worlds, through her observations of how invigorated humans were capable of performing humanity to its fullest during times of crisis.

“Disaster requires an ability to embrace contradiction in both the minds of those undergoing it and those trying to understand it from afar. In each disaster, there is suffering, there are psychic scars that will be felt most when the emergency is over, there are deaths and losses. Satisfactions, newborn social bonds, and liberations are often also profound. Of course one factor in the gap between the usual accounts of disaster and actual experience is that those accounts focus on the small percentage of people who are wounded, killed, orphaned, and otherwise devastated, often at the epicenter of the disaster, along with the officials involved. Surrounding them, often in the same city or even neighborhood, is a periphery of many more who are largely undamaged but profoundly disrupted — and it is the disruptive power of disaster that matters here, the ability of disasters to topple old orders and open new possibilities. This broader effect is what disaster does to society. In the moment of disaster, the old order no longer exists and people improvise rescues, shelters, and communities. Thereafter, a struggle takes place over whether the old order with all its shortcomings and injustices will be reimposed or a new one, perhaps more oppressive or perhaps more just and free, like the disaster utopia, will arise.”

― Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster

8. The principle of thought about The best of all possible worlds somehow harmonises to a certain degree with Buddhist axioms. Buddhism teaches us that we have to recognise and acknowledge that all of creation, from distraught insects to dying humans, is unified by suffering (we can correlate it as the necessary and inevitable evil). Hence Buddhism is all about the confrontation to constant dissatisfaction and how to best approach it if we have no way to escape. Like the Buddha himself, we are all born into the world not realising how much suffering it contains, and unable to fully comprehend that misfortune, pain and death will come to us anytime. As we live, sometimes the reality may be overwhelming, but the Buddha’s teaching reminds us of the importance of dealing evilness directly. We must try our best to liberate ourselves from the grip of our own desires, and recognise that suffering can be viewed as part of our connections with others, spurring us to compassion and gentleness. From a soteriological perspective, this may be the best of all possible worlds - as in a human life, we are able to experience pleasure and agonies of all possible kinds and, transcend these evilness by removing and managing our desires, so we become a better people, together contributing to a better world.

10 April 2020

Feeling of what happens

1. The feeling of what happens is always a recognition, not only an acknowledgement to an external stimuli (a situation, an event), but also a recognition that the stimuli has provoked a bodily reaction within us. Our mind is noticing the body’s reaction to the world and responding to that experience. It is so close to consciousness, one comes with the other - the ability to realise a feeling of what happens comes through consciousness. Feeling is a sensation that has been checked against previous experiences and labelled. It is personal and biographical because every person has a distinct set of previous sensations from which to draw when interpreting and labelling their feeling.

2. Although thinking and feeling are fundamentally different with each other, feeling is intertwined with thinking almost simultaneously. Most of the cases thinking is instantly activated once we are conscious of our feelings, in an unstoppable manner. It is in a rare case that we could purely enter a state of feeling without thinking, be it happen naturally or intentionally. It is because ironically the moment we attempt to stop ourselves from thinking - that instruction from the brain to control ourselves not to think, has already gone through a expeditious thinking process.

3. Once we “feel” something, we immediately start to make sense of of what that is - through thinking. Brian Massumi suggested the concept “thinking-feeling” as a form of thinking, which bears great resemblance to “the feeling of what happens”. It could be understood as an extended and more comprehensive concept of how our brains make sense of the world from the moment we “feel”. In Massumi’s terms, we cannot not see what we’re seeing without also experiencing voluminousness and weightiness—the object’s invisible qualities. The potential we see in an object is a way our body has of being able to relate to the part of the world it happens to find itself in at this particular life’s moment. What we abstractly see when we directly and immediately see an object is lived relation—a life dynamic. We sense or feel the world by including what doesn’t actually appear in front of us, but that is necessarily involved in the thinking-feeling of what does. Once we enter the thinking-feeling process, we go through a self-referential dimension of perception to understand “what happens”.

4. Whenever we feel, we think-feel things like its backedness, sensing also the invisible components that help us differentiate one thing to another. This reminds me immediately the concept of Deconstruction, from which the idea of Différance and Trace stemmed, proposed by the renowned philosopher Jacques Derrida as an approach to understanding the relationship between text and meaning. Each “words” are dependent on each other for their meanings, but that other “words” are always present within the meaning of a single “word”. Take the example of looking up a word at the dictionary. What do we see when we look up a definition of a word - different words, and we look up those more words until eventually we’re back at the first word. The trace, as Derrida called it, is not a presence but is rather a simulacrum of a presence that dislocates, displaces, and refers beyond itself. Isn’t this correspond to the thinking-feeling? When we think about some thing, that “thing” is inextricably connected to other things that aren’t present to give the “thing” its identity. We make sense of the experience of a singular object by virtually drawing connections with many other objects that is associated with that particular object. The trace is in another word the thinking-feeling of what happens in the realm of language.

5. In my perspective this natural process of “feeling of what happens” has a lot to do with our desire to make sense of the world as much as possible, and the fear that we might be confronting to a situation where our systems of attributing meaning has collapsed. It can be described as somewhat a natural mechanism that everyone possesses innately as a human being. Thinking about studying in an art school, one of the main things I learnt in art school is how to continually construct meaning for oneself, be able to deliver that meaning and then allow it to collapse, all while still holding one to a sense of self, perpetually redefining It is indeed a luxurious act that many people nowadays do not have this time and consciousness to involve themselves with. Meanings are usually taken for granted. In the era of ceaseless proliferation of information, people are already overwhelmed with the receipt and assortment of narratives; it becomes a hassle, if not pressure, for one to digest and to evaluate the meanings that are inscribed in what we read and experience. Many of us then habitually rely on the thinking and writing that are available on the virtual internet world and take these as our own experience. We unconsciously repress ourselves from truly feeling and thinking, we no longer develop our own sense of what is happening around us, and that could be a very dangerous act when our “feeling of what happens” is being manipulated.

6. It is because the feeling of what happens always constitute a “reality” and the invisible potential of the experience, there is a leeway for people to dispute on the reliability of the feelings. But what does it actually mean to be detached from reality when the experience and perception of reality itself has its detached side? The semblance (the thinking-feeling of the invisible potential) is perceived as it happens without appearing physically – without being seen or heard. It is always non-sensuously comprehended but being perceptually felt. However this always-already absent present experience and its inseparable existence with the physical reality creates a potential, or even a pretext, for the manipulation and fabrication of “the feeling of what happens”, of the emotions, judgement and reactions that possibly follows. When such strategy is performed, especially by a political power, it can possibly become a doctrine of preemption. Brian Massumi extends this idea of how power nowadays focuses on what may emerge, manipulates the feeling of a potential threat in the absence of an evidence. Massumi names this mode of power that embodies the logic of preemption “ontopower”.

24 Feb 2020

Notes and thoughts on CYBERNETICS

1. Cybernetics is, in the formulation Norbert Wiener gives it, defined as the scientific study of “control and communication in the animal and machine.” Among all notable definitions one could source from the internet up to date, the most influential and remarkable definitions to me are the followings from respectively Ernst von Glasersfeld and Louis Kauffman, the current president of the American Society for Cybernetics :

"The art of creating equilibrium in a world of constraints and possibilities.”

"The study of systems and processes that interact with themselves and produce themselves from themselves.”

2. For every “self-stabilizer", we may find a cybernetic system at operation. What the cyberneticians call a “hyperstable” device, is that a operating system that are capable of self-modulating through the mechanism of feedback, in response to a changing and influencing environment. From how a human body is able to regulate its own temperature, to how an animal learns from its predatory behaviour; pushing to a larger context, to how a business corporation adapt to a change in market condition, and hence to how an economy adjust itself during trade imbalances - all these are illustrations of cybernetics.

3. Writing an essay is cybernetics, considering this at a level of conversation - a conversation in my own head, about what I want to write exactly. These inner conversations with myself within me will inform my actions. By constantly writing and editing to achieve a largely comprehensible text, a feedback loop is employed by myself to understand what I’ve done, and thus improve what i do, and this will become this writing at the end. People who will read this writing may reproduce (some of) what I meant, if so the conversation loop will then extend to involve more than one individual. This can be regarded a the basic nature of society, that we are enmeshed in these conversations which are the foundation of all human and social interactions.

4. Cybernetic concepts often emerged at the boundaries of statistics, physics, engineering, and biology (as a result of the common efforts of various researchers brought together in state-funded researches etc.) The influence went beyond technological societies of the twentieth century. In late 1960s and 1970s, new artistic categories such as “the happening” or “the environment” apart from what may be called a performance. The concepts stemmed from the inflected terms “system”, “process”, “control” and “information” of the then popular cybernetic grammar.

5. The renowned conceptual artist Hannah Weiner may be an exemplar of the artists around 1960s who exhibited an incipient cybernetic grammar in arts. In her first “one-man show” Hannah Weiner at Her Job, there was a text as follows,

"My life is my art. I am my object, a product of the process of self-awareness. I work part-time as a designer of ladies underwear to help support myself. I like my job, and the firm I work for. They make and sell a product without unnecessary competition. The people in the firm are friendly and fun to work with ...

Art is live people. Self respect is a job if you need it. On 3 Wednesday evenings I will be at my studio, where I work. My boss, Simeon Schreiber, will be with me. There will be bikini underpants for sale, at the usual prices, and one made especially for this show by August Fabrics and A.H. Schreiber, to whom I am grateful."

Here Weiner put “I” as an object, which carries the ability to self-regulate and self-produce, based on a cybernetic concept of feedback and control. The notion of self-production and self-objectification is clearly depicted in this shift of “work-art” life. In cybernetics, anything that sustain itself within a constant circular causality feedback, where outputs produce input that subsequently modulate new outputs, is regarded as having a responsibility and capability of self-regulatory, be it a mechanical device or living organism. The ultimate basic definition of a cybernetic entity is that is can become its “own object” achieving its own goal - “a product of the process of self-reflection”.

6. It appears that cybernetics is the algorithmic system of almost everything - physical, technological, biological and social systems. It is theoretical, at the same time the knowledge processes are convertible into actual technological software for practical executions. After all it is about the science (and art) of systems that has a purpose and cybernetics itself is a theoretical implementation assisting any systems to “act effectively to achieve its goal”. Karl Popper in his book A World of Propensities, has a very similar cybernetic perspective when he explains the concepts of causality and evolution, that “We learn by trial and error, that is, retroactively.”

7. While we might imagine when there is no hierarchy exists at all, that every individual is included in a cybernetic system, a subconscious consensus will thus be formed and a new kind of democracy (equilibrium) will be created. Yet this is only a radical individualism and utopian theory about computer systems. When implemented in a social and economic context, in spite of the theoretical goal of cybernetics as a reflexive control of actions to attain an equilibrium, in another word, a common culture in a meta-view; it’s key components “control” and “communication” is often manipulated in systems and corporations where hierarchical, multilayered management exists in reality. Thus cybernetics became a popular means of managerial strategies to corporates, institutes, military, government technocrats as it promotes an efficient and effective means of achieving certain goals through complex processes.

8. The concept of cybernetics has its origin in military research, from attempts by Norbert Wiener and colleagues to develop self-adjusting antiaircraft guns, the science of “control” is then amplified. However cybernetics could often present itself as an integrated organic mode of social regulation, embracing democratic values and promote the empowerment and involvement of all. As Fred Turner writes in From Counterculture to Cyberculture, cybernetics provided “a vision of a world built not around vertical hierarchies and top-down flows of power, but around looping circuits of energy and information.”

The power of cybernetics, when applied in a social context, is irrefutably its ability to dissolve deviations and contradictions, through conversations (internal or external) to achieve an agreement of mutual consensus between opposed entities. The self-regulatory system evolves into some larger entity that includes both sides. Fred Turner used the famous poem of Richard Brautigan - All Watched Over by Machine of Loving Grace, a poem which Brautigan has been giving out for free in the 1960s and has been well received by the society - as an example of this harmonic holistic ambition of cybernetics:

All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in a mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computers

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

In the poem the idea of a concord between human, animals and electronics is clearly described, a the result of a cybernetic society or ecology is proposed as a dissolution of the seemingly oppositions between nature and culture, living and non-living beings, labour and life. Yet, the last sentence of the poem appears to me a foresight (given that the poem is written decades ago) of the idea that we will all be living under the surveillance of these machines if the society is a cybernetic one. Is democracy then still attainable once the control of the machines (surveillance) is taken into account as a power control? If we are “free of our labours” does that necessarily lead us to a better life?

1. Karl Popper, A World of Propensities (Bristol: Thoemmes, I990),p.IZ. 2. Peter Galison, The Ontology of the Enemy: Norbert Wiener and the Cybernetic Vision, Critical Inquiry 21, no. 1 (October 1994): 228–66. 3. Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 38.

31 Jan 2020

The Faith of Exposure

Eve Sedgwick introduced in her essay “PARANOID READING AND REPARATIVE READING. OR. YOU ARE SO PARANOID. YOU PROBABLY THINK THIS ESSAY IS ABOUT YOU”,

the paranoid as a prevalent contemporary mode of critique, that we presume too often that the process of demystification is the goal of social and ideological critique. Sedgwick defined paranoia in this knowledge-generating process with five key elements, one of which is ‘paranoia places it faith in exposure’. What she means is the seeming faith of knowledge revelation - when a piece of information or idea becomes more and more transparent, then and only then will there be any significant effects.

Since paranoid readings are those that ultimately only confirm what is already known, as Sedgwick put it “they insist that bad news be always already known.” The act of exposure then serves as a theoretical terminus ad quem in itself without any possibilities of alternative thinking and organising. As a psychic defence mechanism, paranoia attempts to stress on a pre-emptive knowledge of a possible violence, the successful exposure of that violence results ironically in a triumphant grand narrative that basks in the process of unveiling.

When violence as a problem is made visible through paranoid exposure, that exposure often changes it and expands it, very often also problematises it. There is this undeniable paranoid assumption that people have to see the painful effects of their oppression, poverty, or deludedness sufficiently aggravated as the only way to “validate” and “awaken” the consciousness of the pain, so as to emphasise on the intolerable situations as if the more intolerable it is, the more efficient to generate “solutions”.

In paranoid criticism it is easy to fall into a trap of demystification and exposure, only arriving to a mere (anticipatory) knowingness. This faith in exposure is often implicit in what goes by the name “critique” despite the little constructive judgemental consequences it may bring.

"For a long time, some people believed that if the horror could be made vivid enough, most people would finally take in the outrageousness, the insanity of war.”

- Susan Sonntag, Regarding the Pain of Other’s, 2003

Exploitation of the suffering (of others)

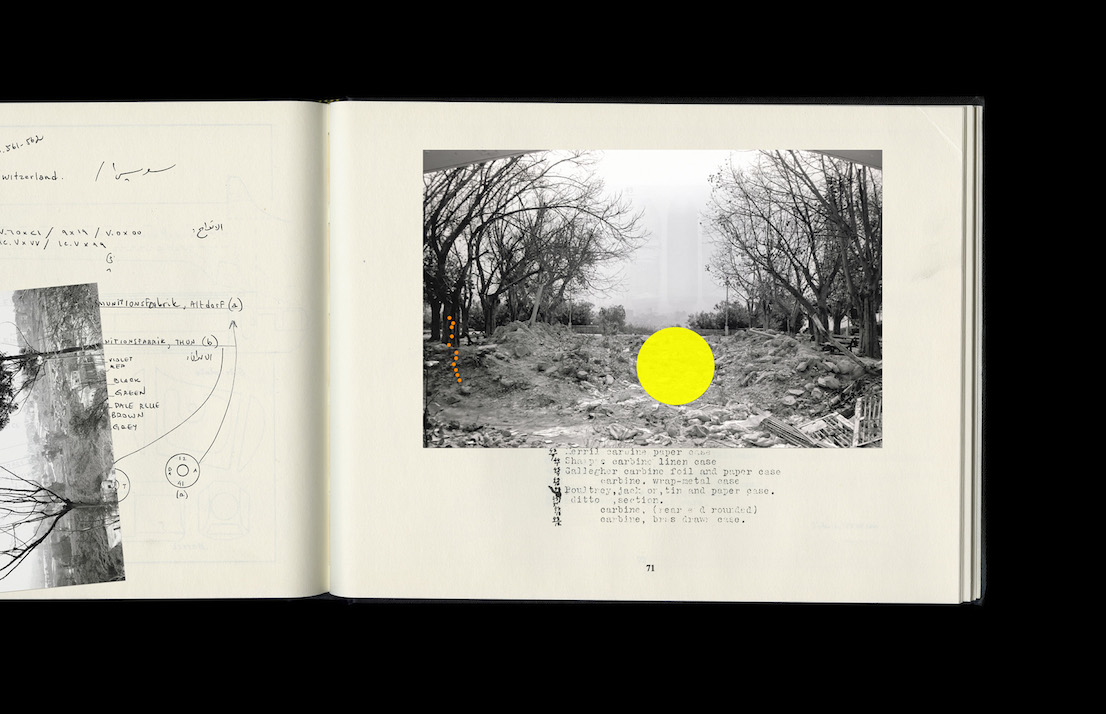

Considering the faith of exposure in an artistic context, Walid Raad’s (under the name of the Atlas Group) “Spectral Archive” popped up in my mind. In collecting and archiving testimonies and documentations related to the contemporary history of Lebanon, the Atlas Group aims to analyze yet unexplored dimensions of the traumatic experiences of the Lebanese civil wars that raged through the country in the past decades.

Raad often presents the works as a fiction from the very beginning, in a well-composed mixture of fabricated and found documents. Rarely is there an explicit depiction nor detailed description of the terrifying and outrageous facts in the wars, but archives of testimonies around all the violence (Documentation of Lebanese historians killing time at the racetrack gambling on finish-finish photos, while bombed are being deployed throughout the country; documentation of police tasked with investigating crimes of car bombings, fixating instead on the particular trajectory of the engines launched from those vehicles.). The confusion is what will either attract one to his works, or force one to hold it at a suspicious distance. I wondered why exactly this approach? Why not just speak about the blunt and violent material evidences without all the fictionalizing, constructed characters and testimonies? Is trying to understand the distressing event that has happened (be it socio-economic, historical, political) enough? Is trying to render justice enough? No, justice is never truly attainable and is never enough.

Soon I learnt from the works that fiction(s) can still be convincing, even when from the beginning one knows it is unreal. It's an interesting yet conscious and critical direction. In Raad’s case by not focusing on the exposure of the violent and traumatic historical evidences, he persuades the audience not the failure of images to represent traumatic events, instead focusing on the investigations of the refusal of the real to inscribe itself as a legible image. In the works, the ambition is not necessarily fame or the rehabilitation of a missing narrative or even the satisfaction and possible impact that comes with comprehensive knowledge accumulation. When we try to discuss the topic from a perspective in which violence and the brokenness of subjects are obvious and spectacular, not hidden, do we always focus only on the relationship between visibility and recognition (legal, social, political)? Truth doesn’t necessarily lead to recognition, not to mention reconciliation; and Raad is obviously very clear about that thus incorporating fictional devices to deal with the distant detached topics of cruelty and suffering for many of his audience. I understood it as an alternative approach, almost a reparative one, one that approaches reconciliation outside a juridical economy of truth.

Apart from acknowledging what have happened and might have destroyed us, maybe it is as well important to also feel that we merit the event that happened to us, and this may have something in common with what Sedgwick proposes as “reparative reading”. When violence and suffering is so on the surface (especially to victims of the context), and being so over-saturated in this era of technology, what is there to necessarily further uncover and put it on display? Is it always necessary to dig deep into the root of the question, to return to the origin so as to proceed for a resolution? Maybe it is time to experiment the opposite (or alternative) methodology - to uncover what is being said despite the violent facts. So what is the appropriate hermeneutics when the goal is not of uncovering a hidden history of trauma, but hearing what the traumatised person is saying? This then becomes a question of the future. It is a question of the production and amplification of a narrative that may not be historically factual, but real to those who has overcome the experience, true to the subjects and has inscribed in their memories as part of the event.

Walid Raad, The Atlas Group, Let’s Be Honest. The Weather Helped Switzerland, 1998-2006. Courtesy: Walid Raad e/and Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut/Amburgo

Fire Works, 2020

Dark night

reworks horizontally deployed

from just around the corner

of where i escaped

from fear but arrived to estrangement

invisible sparks with bombing sounds and colours smoke

gets into the eyes of innocent ghters

in the town where I grew up

LOUD

BOMBING

SOUND

EXPLODE

BURN

BLOSSOM

Fire works

working at its best

i heard them in the dark

i saw them from afar

i even smelt them

in my imagination

in the speechlessness in the light

of the harsh reality of the war.

Fire Works, 2020

Fire Works, 2020

Dec 2019 - Jan 2020

Democracy

Never have I witnessed

A collective desire that strong

A solidarity to resist the authoritarian control

A pulsation that longs for cohabitation

Civilians, ethnic minorities and majority (Muslims, Buddhists, Catholics), white collars to peasantries, juvenile to retired

Forming the basis of consensus

The awakening of the “silent majority”

The outbreak of the popular will

The political principle follows from the confrontation to the power and the very determination of the desire to persist in one’s own being

In accordance to Spinoza’s view,

One desires to persist in one’s own being only if one is aware of the others and the relation herein

Without this susceptibility there will not be any persistence

In a city like many metropolis and community out there

Democracy is currently threatened, in all possible means, obscurely or ostensibly

A city that occupies only a dot on the map

A once-colonised city that has never been so close to the Chinese despot

A city so enraged and distressed

Demonstrations of hundreds of thousands, marching into the hundredth day and night and counting

Under the performance of Nationalism from the North

To be exact

Authoritarianism interwoven with militarism and neoliberal state capitalism

Demonstrations are abbreviated versions of the democrats

Who stand as one to lay claim to a popular status

In defiance of its potential negation

To assert the accountability of the state to the people it claims to represent

To delegitimize a regime that seeks to lay claim to the brutal facist control

To engage in decision making that have always been taken without any open consultation or true participation

Through negation also to speak up for those who cannot appear, who have been made disappeared, whose right to appear does not exist

It is by virtue of our social dependency that we all are vulnerable

We know of its suppression and repression by the states or non-state forces, local and foreign

In places like Chile, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Bolivia, Ukraine, Serbia, Colombia, East Turkestan, Tibet, so on and so forth

We know that Democracy is our mutual goal

Our only chance to reclaim freedom from authoritarianism

Our determination to fight against humanitarian crisis

As Seneca says, No one can long retain a tyrant’s sway

It is Democracy that preserves men’s natural equality and natural freedom

When men hand over their individual sovereign power of self-defense and liberty to one

In the hope of some greater good, and in the fear of some greater evil

The body politic then possess sovereign right over all things

As a society which wields all its power as a whole

Spinoza’s political philosophy is a loveable one

For its ideal definition of Democracy which based on trust and positive affects

It is only True Democracy that aims to create a state of its freest

Where laws are founded on sound reason

To bring men as far as possible to liberation under guidance of reason

To avoid irrational desires that restrained men being free

To cherish good faith above all things as the preservation of the state and its people

Then all men remain, equal and free

Shall this basis be removed

A seduction of deceptive shortcut to freedom

A breach of faith

An obsession to domination

The whole community falls to ruin

By Democracy I mean no tyranny’s discourse

For Democracy, Justice, Human Rights terms as such have been recurrently abused by the authorities

John Berger once wrote, Democracy is a proposal (rarely realised) about decision making; it has little to do with election campaigns

To pursue true democracy private civil rights must be enforced

A democratic state can no doubt retain their power by consulting the public good and act according to the dictates of reason

Yet we see now the trickery falls in here

Before voices of the civilians could be heard and command rationally

Those being governed ought to have to be adequately informed about the issues in order to command

Democracy,

Nowadays often as a deceit for freedom of binary choices, filtered information, erased history

Is used as pretence of legality to deprive men of their rights

For decision-makers no longer embrace the benefits of freedom and commonwealth in a state

For faith and respect are no longer valued under the edict of the sovereign power

And by all means we shall not stop contesting and confronting the tyranny

When dialogue with it is almost impossible

When doctors, journalists are arrested

When universities is condemned as “cradle for criminals”

Dictatorship put justice and democracy to death ropes

Saddening similarity of political power across the world

Revenant of obliteration

Warrior of oppression

Let us reclaim our words, our values, our society

Be it democracy, equality, suffrage

Let us hold on to the perseverance of one’s own being

Our desire to live

11 Nov 2019

Historical Bloc as a potential revolution tactic

The concept of historical bloc has become popular because it refers to a progressive phenomenon during a change, when a new political party has been built, and it is seeking to establish a hegemony. To do so, this uprising social class, through its political party, has to organize other social classes and political parties as well to take part in their wider political, economical alliance, which in theory defined by Gramsci as “historical bloc”. In this process, the organic intellectuals of the political party play a fundamental role in introducing persuasive ideas and arguments in order to convince other classes to be a part of their historical bloc, thus their upcoming hegemony.

Historical Bloc is regarded by some a position showing the complexity of the social whole as the terrain of political intervention. Thus it carries a potential practicality not in the sense of an abstract theoretical justification of political and social change, nor in the sense of simple anticapitalist rhetoric, but in fact it can be a practice to be carried out as a set of original and necessarily experimental steps that will lead from the break with original exercising mode of power to a new political and socio-economic alternative.

If the relationship between intellectuals and people-nation, between the leaders and the led, the rulers and the ruled, is provided by an organic cohesion in which feeling-passion becomes understanding and thence knowledge (not mechanically but in a way that is alive), then and only then is the relationship one of representation. Only then can there take place an exchange of individual elements between the rulers and ruled, leaders and led, and can the shared life be realised which alone is a social force – with the creation of the ‘historical bloc’.

The politics of putting forward a historical bloc can be seen as the articulation and combination of political strategy, transformative actions, alternations or interventions, ideology (or beliefs) and in certain extent forms of organization, it comprises all the practices that would potentially help the subaltern classes becoming a historical force and initiating a process of social transformation. In that sense we move from mere resistance of the existing situation to constructing an alternative, a potential resolution.

Such an act can be a powerful knowledge gathering, re-organizing and re-affirming process, both in the sense of using the knowledge accumulated by people in social movements and also in the sense of struggle, solidarity and common beliefs being forms that help people share and spread knowledge, incorporate new perspective and collectively re-establish new forms of intellectuality and eventually a cultural hegemony. I believe this is a way of understanding and exercising the “organic cohesion in which feeling-passion becomes understanding and thence knowledge” and in turn transformative social and political practice.

It is an attempt to rethink revolutionary strategy as an open-ended sequence of transformation and experimentation, and whether or not a “hegemony” would be the ultimate destination is only to be found out until then. However, it is always easy to suggest strategy as rhetorics, but it can be hard to even imagine, not to mention to gain a common consent for confidence and experimentation to an open-ended process of social transformation.

Definition of the concept

Gramsci first introduced the concept of Historical Bloc, in association of the concept of Hegemony, to analyse on the forms of political power, the concrete relations between social classes and political representation, and the cultural and ideological forms in which social antagonisms are fought out or regulated and dissipated.

A historical bloc exercises hegemony through the coercive and bureaucratic authority of the state, dominance in the economic realm, and the consensual legitimacy of civil society. Gramsci used the term historical bloc to refer to the alliances among various social groupings and also, more abstractly, to the alignment of material, organizational, and discursive formations which stabilize and reproduce relations of production and meaning.

14 Oct 2019

Body without Organs

“The body is the body/ it is all by itself/ and has no need of organs/ the body is never an organism/ organisms are the enemies of the body.”

This quote from Antonin Artaud is reiterative of the definition and is indeed the derivation of the concept of Body without Organs by Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus.

Here we first have to understand the Body and Organs. Everyone has a body. In fact we could say everything are bodies. Humans, animals, countries, microbes, etc., all have bodies and therefore are bodies. Of course, all bodies are made of other parts, like the human body which is made up of various parts such as organs. Organs, are the physical or actual parts that constitute a body - organism, biological parts, organisation, solidity. Yet, a body is not just its actual side. A body is also its Body without Organs, which refers to a virtual dimension - virtual singularities, potential, fluidity.

For Deleuze and Guattari, every actual body and its energy is captured by countless desiring-machines and their organisations, which desire to be freed up. Desiring-machines fill the body with patterns of satisfaction, while at the same, it tortures the body by trapping it in connections with flows that necessarily stagnate and rot. The Body without Organ, is a force that is then constructed through the activity of the desiring-machines themselves, however it is also the force that propels desire away from actual connections.

The Body without Organs, on one hand repels desiring-machines - transforms current and actual desiring-machines into repulsion-machines; and on the other, attracts the production of new connections - transforming potential desiring-machines into attraction-machines. Hence the Body without Organs frees up libido in order for it to get new charges. For every connection, a Body without Organs, a disconnection. This process is essential and inevitable to ensure for new production, production of production.

In another words, every actual body has a limited set of rules, traits, habits, movements, etc. But every actual body also has a virtual dimension: a reservoir of potential traits, connections, affects, movements, etc. The Body without Organs is thus potentiality. The Body without Organs desires for and are virtual potentials for future satisfactions.

1. On literal Body (of the schizophrenic) :

Antonin Artaud declared war with the organs in To be done with the judgment of God, "for you can tie me up if you wish, but there is nothing more useless than an organ.”

According to Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus - The full body without organs is "schizophrenia as a clinical entity”. Another quote from the text where it said, “Thus the schizophrenic, the possessor of the most touchingly meager capital — Malone’s belongings, for instance — inscribes on his own body the litany of disjunctions, and creates for himself a world of parries where the most minute of permutations is supposed to be a response to the new situation or a reply to the indiscreet questioner.”

Schizo desire can be understood as inscribing or synthesizing a variety of permutations that the body can pursue and experiment with. This is exactly the default setting of desire — it longs for the production of something new. When we see a literal schizophrenic doing what he/ she does, it often appears to be some intense, frantic, abundant drive towards to something “abnormal”, something new and different. See that, smell this, touch here and there. It’s a relation to the world that operates in a type of overdrive. It defies any of the boundaries we seek to impose on it and we are in a way “too conventional” to keep up with it. The schizo’s responses to our inquiries are creative and indiscreet, at times playful.

2. On Theoretical Body :

“As in the case of Beckett’s mouth that speaks and feet that walk: “He sometimes halted without saying anything. Either he had finally nothing to say, or while having something to say he finally decided not to say it. . . . Other main examples suggest themselves to the mind. Immediate continuous communication with immediate redeparture. Same thing with delayed redeparture. Delayed continuous communication with immediate redeparture. Same thing with delayed redeparture. Immediate discontinuous communication with immediate redeparture. Same thing with delayed redeparture. Delayed discontinuous communication with immediate redeparture. Same thing with delayed redeparture.” “

This description from the text is very helpful in a way it illustrates how the mouth and the feet experiment with each other. Trying out new experiences in relation to one another. As simple and mundane as this sounds, this is how new connections could be produced. The body is slightly modifying itself in order to reach out possible experiences of satisfactions.

This is what they called a series of “either…or…or…or”. Since the actual experience of talking and walking are inscribed on the Body without Organs, they are stored as virtual data of the body, and from there the Body without Organs constructs potential differences and modifications between the actual experience of walking and talking. “What are all of the different ways talking and walking can actualize themselves in new experiences?” All of the potential permutations are constructed then. However, instead of re-actualizing, regaining, re-presencing some lost information from the past, new variations are being generated. The Body without Organs is thus oriented towards the future instead of fixated on the past.

As defined in the text, the Body without Organs is not an original primordial entity, nor what remains from a lost totality, instead it is the "ultimate residue of a deterritorialized socius".

Every actual body (and of course the Body without Organs) desires freedom, deterritorialization, liberation and dis-organization. We can understand organization as the actual - rules, routines, patterns, habits etc., and dis-organization on the other hand the virtual - possibilities. An essential idea about the Body without Organs is a body without organization, that operates without fixed and repeated structures. In a sate of dis-organization means a body establishes itself constantly in new relations and configurations. The Body without Organ is an opposite of some fixed, static, solidified patterns or structure, it morphs as a state of becoming, and should be able to take on all kinds of different shapes.

3. “How do we become a Body without Organs”

When you will have made him a body without organs,

then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions

and restored him to his true freedom.

They you will teach him again to dance wrong side out

as in the frenzy of dance halls

and this wrong side out will be his real place.

– Antonin Artaud, To Have Done With the Judgement of God, 1947

This is where Deleuze got the literal idea of Body without Organs. Deleuze also was intrigued by the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza : “no one yet has determined what the body can do” - we can do seemingly impossible things with bodies.

We all, as human beings, by definition from Deleuze and Guattari, are automatically Body without Organs, be it conscious or unconscious. We may say the body without organs is an inevitable exercise or experimentation, already accomplished the moment we undertake it, and it awaits us. We are already on it, on it we live, we sleep, we fight and are fought, we seek our place, we experience, on it we penetrate and are penetrated, on it we love. It is not at all a mere notion or a concept, but a set of practices.

To "make oneself a Body without Organs," then is to actively be aware of and experiment with oneself to get rid of any rules and activate all virtual potentials. The Body without Organs demands that we embrace diversity and complexity. When one no longer needs the morality of oppression that biology and society forced upon oneself, then one would be free to do more with our bodies, actualise more possibilities through interacting with other Body with Organs, hence “shed one’s innards” and rebuild from the outside in.

In conclusion, we are the being that can actively expand our Body with Organs. We can do things that help enable the body to transform and become. As Deleuze and Guattari stated in Logic of Sense,

Lodge yourself on a stratum, experiment with the opportunities it offers, find an advantageous place on it, find potential movements of deterritorialization, possible lines of flight, experience them, produce flows of conjunctions here and there, try out continuums of intensities segment by segment, have a small plot of new land at all times.